Impact Stories

Connect With Our Experts

Seeing the Kingdom Manifest

One man’s extravagant generosity is helping send missionaries like Thomas Sieberhagen and Amy Jones to a world that’s never needed the Gospel more.

ON THE FIELD – The Sieberhagens’ church plant is based in the city of Namur, the capital of the French-speaking southern region of Belgium, with a population of about 112,000.

Sieberhagen had been a follower of Christ since early childhood, but during those trips he began to feel it — to crave an eternal reality that was vastly different from the world’s. “It was those moments where I first started truly longing for a Kingdom where orphans are sons and daughters of the King,” he says. “That desire to see His Kingdom manifest on the earth was there early.”

FAMILY BUSINESS – The Jones family – (left to right) Casey, Evie, Clair, and Amy – is diving into the local culture in Leipzig as they reach the German people for Christ

“I realized I didn’t have the power I needed to do good,” she remembers. “I could tell there were certain people who had this strength about them — to do good, to love and care for others. I didn’t have that. In my own little kid way, I remember talking to God and saying, ‘I know I need you.’”

Both Sieberhagen and Jones share childhood moments of clarifying purpose, but it isn’t the only thing linking them. They both pursued lives as missionaries, moving with their families to Europe and planting churches in cultures radically opposed to the message of Christ. They both received theological training at Southwestern Baptist Theological Seminary in Fort Worth, Texas. And they both benefited from an unlikely source of profound generosity: Richard Estes.

Seeds of Purpose

When the people who knew Richard Clark Estes use the word “quirky” to describe him, it’s a term of obvious affection. His legacy is undeniable: millions of dollars in charitable giving to train those taking the Gospel to the furthest reaches of the earth. But there are some interesting contrasts between him and those he’d eventually fund. Estes lived a life on foot, spending his evenings strolling the sidewalks in his hometown of Bartlesville, Oklahoma. He worked in the research and development department at Phillips Petroleum Company until 1986 and maintained a strong connection to Bartlesville First Baptist Church. Music was among his passions; he played the piano and organ and sang in the church choir.

The idea stuck, and Estes began working with WatersEdge to make this dream a reality. He learned about the possibility of leaving a lasting gift through an endowment — a giving mechanism designed to multiply a donor’s contribution many times beyond its original value, providing a nonprofit ministry or organization with a perpetual stream of revenue. Estes decided his endowment would fund a scholarship for students at Southwestern Seminary that were heading to the mission field. He began building the endowment while he was still living, making gradual donations that grew through investment. It was a modest account at first, with an initial gift of $1,000, but it didn’t stay that way for long. Today, his endowment — which Estes named in honor of his mother — is worth almost $5 million. Since 2014, it has distributed over $1 million to more than a hundred Southwestern students, including Thomas Sieberhagen and Amy Jones.

For his part, Estes was always humble about his giving. To him, it was a way to honor his mother’s legacy and her Kingdom impact. But for those who’ve benefited from the scholarships, it’s nothing short of radical.

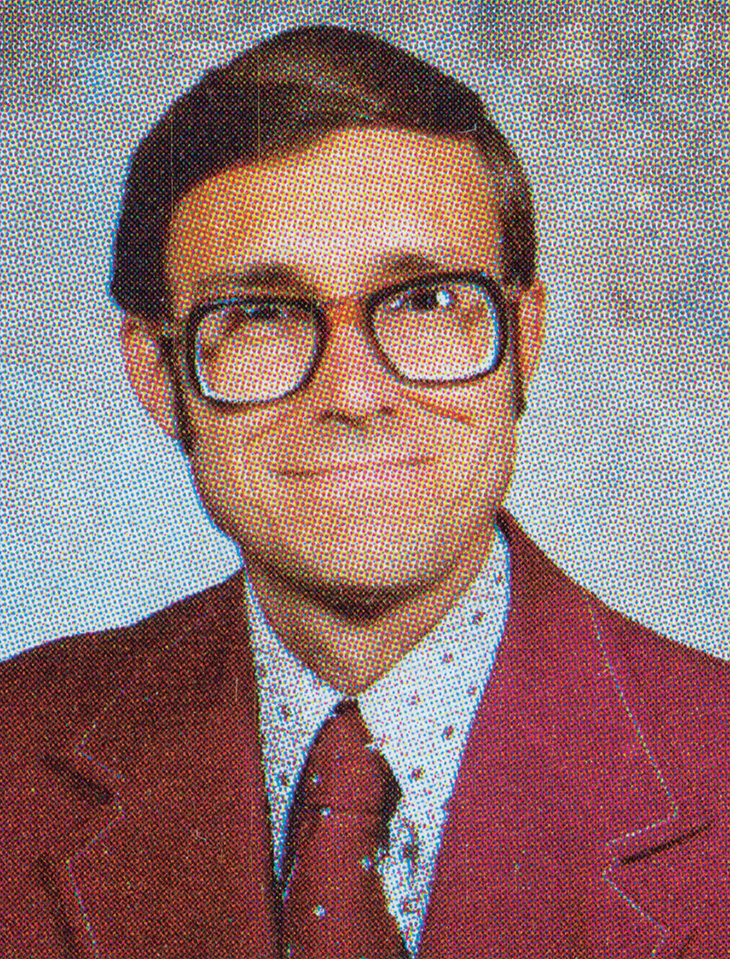

UNASSUMING GENEROSITY – Richard Estes, pictured here in the directory of Bartlesville First Baptist Church, where he was a faithful member for decades.

The scholarship was a validation of the calling felt by Sieberhagen and Jones, a divine provision to help them take the Gospel to a lost world.

ALL SMILES – (left to right) Thomas, Ransom, Primose, and Holley Sieberhagen pose for a family photo on the campus of Southwestern Baptist Theological Seminary in Fort Worth, Texas, where they’re currently serving as missionaries-in-residence during stateside assignment with IMB.

Paving the Way

Jones never lost sight of that calling, even throughout her early life and education. When she went to the University of Tennessee to study music, the idea of mission work was never far from her mind.

“While I was deciding what I was going to do in college, I thought, ‘I’m called to missions. What does that look like in my life? I’m a missionary, but what’s my job title going to be?’” she remembers.

After graduation, Amy pursued her master’s degree in missions at New Orleans Baptist Theological Seminary, and the timing coincided with Hurricane Katrina. She dove into the relief effort after the storm, thinking that maybe this could be her calling — a lifelong, Gospel calling.

“I really thought my life was going to be helping replant churches in New Orleans,” she says.

It turned out she was right about church planting, just not in New Orleans. A mission trip to Moscow during the last year of her master’s program reminded her of the Gospel burden that existed abroad, and it reignited her passion. “Every day, I shadowed a different missionary there,” she explains. “They had different daily lives, different strategies, but they were all on mission, and the lostness I saw broke my heart.”

Once she completed her master’s degree, Jones served as a missionary for two years in Vienna. While there, a mentor encouraged her to pursue a second advanced degree, and Jones started looking at options. Southwestern Seminary wasn’t even on her list until she visited campus for an expo.

“I was pleasantly surprised,” she says. “Both with the programming and with how open they were. They treated me like a colleague.”

She trusted her instincts and made the decision to attend, and that decision paid off tenfold — literally, via the Myra Cross Estes Memorial Scholarship. In addition to receiving the financial freedom that came with the funding, Jones met her husband, Casey, and had two children — Evie and Claire. By the time she finished her masters in theology, the family’s plan was clear: they were off to Leipzig, Germany, to plant a church through the IMB.

SPREADING THE WORD – As missionary-in-residence, Sieberhagen has the chance to encourage others on the path to the mission field at Southwestern Seminary, as well as report on the growth his team is seeing in Belgium.

Not on Earth

For Sieberhagen, the call to missions didn’t necessarily include leaving home, mostly because “home” was always a nebulous term. He was born to South African believers, but he didn’t stay there long. His parents moved twice during his childhood — once when he was 5, to pursue ministry in the United States, and again when he was 8, to Kazakhstan as missionaries. Looking back, he’s grateful for the transient childhood because it serves as a reminder of a difficult biblical truth.

“We have so many indications in Scripture that our citizenship is not here on Earth,” he says. “That ‘home’ feeling is only going to click 100 percent in Heaven. In many ways, this freed me to be able to accept the call to missions much more easily, because I didn’t have strong roots here in the States.”

“She was baptized when she was 10, and the Lord radically spoke to her and said, ‘I want you to be a missionary,’” he explains. “She barely even understood what that was, but she was obedient.”

The couple moved to Fort Worth immediately after college, and Sieberhagen received the Estes scholarship while studying for his Master of Divinity. Afterwards, he and Holley moved to Namur, Belgium, where they’re part of a church plant with another IMB couple.

FIRST STEPS – The Jones family enjoys a reception following their appointment as missionaries at the 2017 IMB Sending Celebration in Richmond, Virginia.

Planting in Hard Places

In many ways, both Sieberhagen and Jones are dealing with the same cultural challenges in Namur and in Leipzig — a post-Christian culture that’s not even sure how to talk about the spiritual realm, much less engage with the Gospel. Less than 1 percent of Belgium’s population could be classified as evangelical Christian. Germany’s numbers are higher, but there’s another cultural challenge in Leipzig: history.

“In our area, the Soviet regime was incredibly damaging,” Jones explains. “Anybody over 50, if you try to have a spiritual conversation, they may physically flinch, because they’re that nervous about talking about eternal things.”

“Most Germans are spiritually hungry, and they have absolutely no idea how to feed themselves,” she says. “If you ask somebody what they believe, they’ll say, ‘I don’t believe in anything.’ But if you ask if they have spiritual practices, they’ll say, ‘Well, I’ve studied astrology, I do tarot cards, I’ve practiced yoga …’ You can tell they’re seeking; they just don’t know how to connect those activities with their soul.”

A similar hunger exists in Namur, along with the same trepidation for broaching spiritual conversations. “The people we talk to, their grandparents stopped going to church,” Sieberhagen explains. “They themselves are many generations removed from any kind of biblical literacy whatsoever. The first hurdle you have to jump, then, is to convince them that spirituality has a place in their lives at all.”

Either field could be discouraging for a missionary, but that’s not the case with these teams. Sieberhagen acknowledges this is simply the reality in 2022. “It’s a hard context,” he says, shrugging it off. “You know, the IMB says there are no easy places left. If you want to go as a missionary or to plant a church, there are only hard places.”

But given a few years’ time and the movement of God, both Sieberhagen and Jones are excited about the fruit they’ve seen through their respective church plants. The Namur team rents a space to use as an art center, getting people in the door through exhibits, Gospel choirs, and other events throughout the week; on Sundays, they host church gatherings. In Leipzig, Jones’ team rents a storefront as a church building in an especially challenging neighborhood — they’re literally across the street from a Communist compound.

Both couples are grateful to see God working in difficult places, and pessimism isn’t an indulgence Sieberhagen or Jones allow themselves. They’re young, passionate about the work, and excited to see the Spirit continue to move when they return.

COVERED IN PRAYER – Sieberhagen and other IMB missionaries meet during Southwestern Seminary’s Global Missions Week to pray over their respective countries and people groups.

“Yeah, it’s not thousands of people coming to know the Lord in Namur,” Sieberhagen says. “But it’s tens of people, which is more than Belgium has seen in decades, really.”

Jones echoes this ethos: slow, consistent growth by engaging with people’s questions. “They’re hungry, and they want to do something, but nobody has taught them,” she says. “We can’t wait to dive in again with our church plant.”

Legacy can be a fascinating concept, especially in matters of faith. The Sieberhagen and Jones families are building spiritual legacies, a foundation of faith they pray will stand strong for decades to come. Richard Estes built a legacy, too. He’ll never walk the streets of Leipzig or converse with someone in a Namur art house, but the generosity behind his endowed scholarship will continue to make an impact in both of these places, and other mission fields around the world, for generations to come. Men and women will give their lives to Christ at these church plants, never knowing they can track part of their spiritual lineage to a singular man in Oklahoma, quietly doing what he could.

They won’t know, that is, until Heaven.

Give the Gift of the Gospel

Richard Estes’ generosity started with a single gift of $1,000 and has grown to support missions work around the world. If you’re interested in creating an endowment to support Southwestern Baptist Theological Seminary — or to assist another ministry you’re passionate about — our giving professionals can help you multiply your gift and maximize tax benefits. Start a conversation with WatersEdge today.

give@WatersEdge.com | 800-949-9988 | WatersEdge.com